This note is largely based on a paper published by Gretzinger et al (2022). The authors deal with a variety of issues. However, I only look at their primary focus, ie the most likely European origin of pre Viking English people (as opposed to Celtic people). The details of that research are given in their Supplementary Information, Supplementary Note 3.

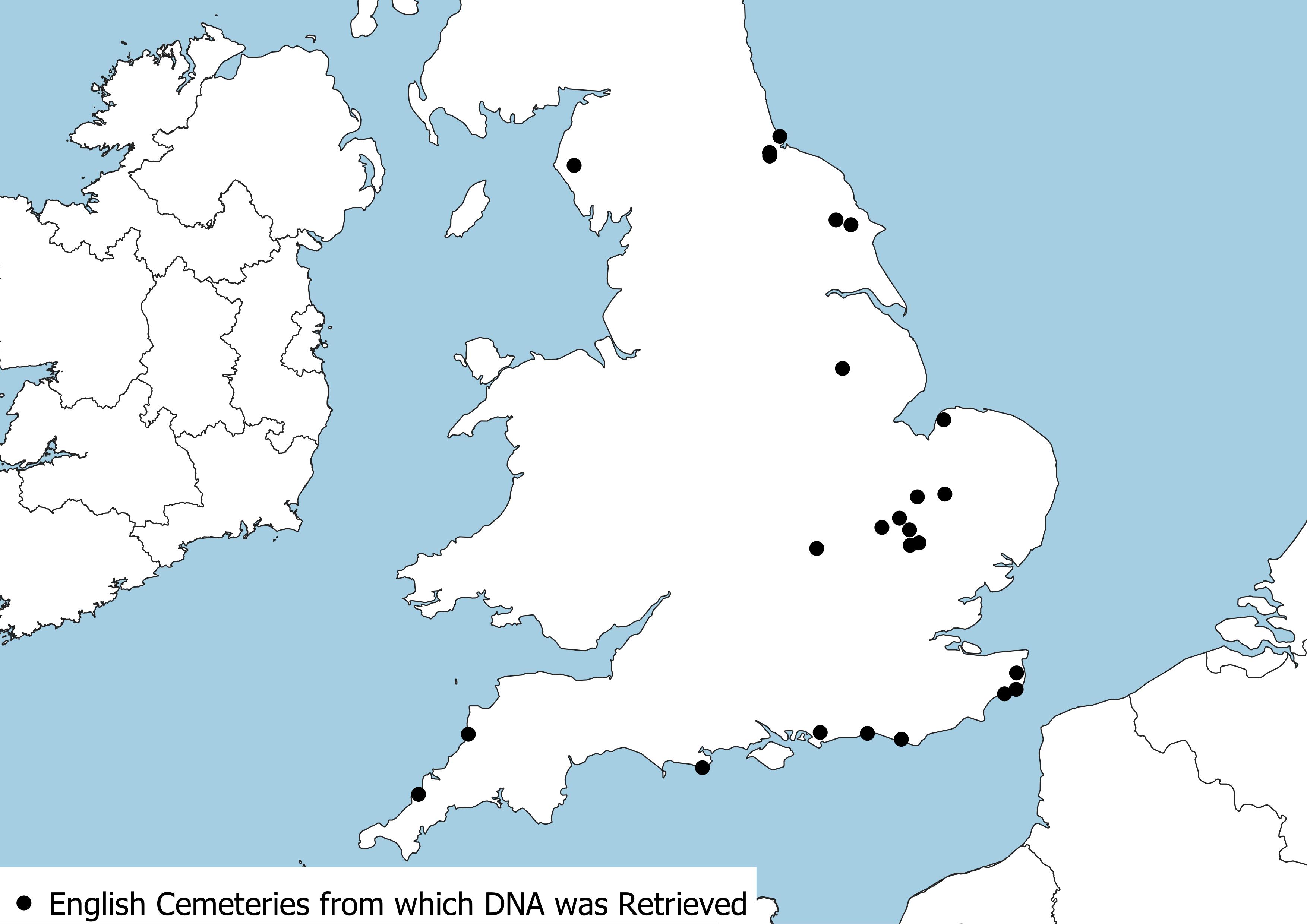

Genetic material was retrieved from individuals found in the places listed in Appendix 1 and shown in Figure 1 below. Each individual’s DNA was analysed to identify the proportion of WBI (referred to here as “Celtic”) ancestry versus CNE (referred to here as “Germanic” and including Scandinavian) ancestry. The majority of sites were in the East or South with clusters in Cambridgeshire and Kent. There are significant gaps in the North, Mercia, the Home Counties and the South West.

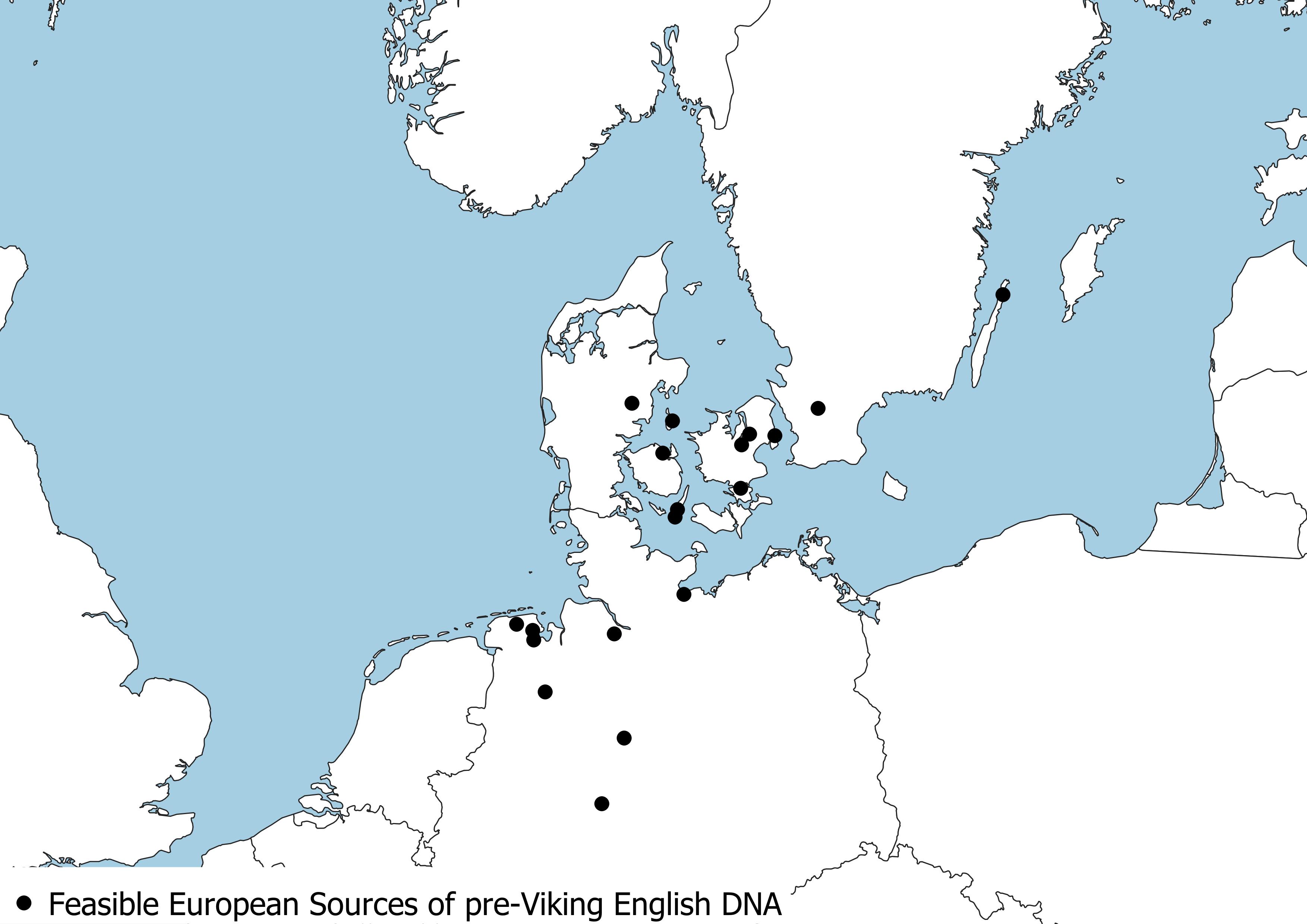

The authors report two methods used to identify likely European origins in their Supplementary Note 3. The first method only uses DNA from the 109 individuals having very high levels of Germanic ancestry.

The second method uses DNA from all 285 individuals, Celtic, Germanic and mixed. It balances out the effect of the Celtic ancestry by also including Iron Age DNA (ie from before the arrival of the Germanic people) in the statistical model. This allows the Germanic origins to be separated out.

The results from both methods are similar as shown in their Supplementary Figure 3.9a. This figure overlays the results from the two methods. For clarity I only reproduce the results from a single method. See my Figure 2. I used their method 2, primarily because the detailed origins are given in Figure 3.9b.

These results will be surprising to many, particularly those who believe that a continuum of Germanic peoples were involved in the invasion of England, and that those peoples came predominantly from Danish Anglia and adjacent areas in Germany and the Netherlands. What is particularly surprising here is that the genetic origins include places from the far north east of Denmark and into Sweden. Unfortunately there is a shortage of DNA reported from Angeln to test the “continuum” hypothesis. The only site in that area shown on the authors’ Figure 3.9a appears to be in the neighbourhood of Schleswig itself. This site does not show a strong association with Early English DNA. Inevitably the DNA they use is restricted by the availability of samples.

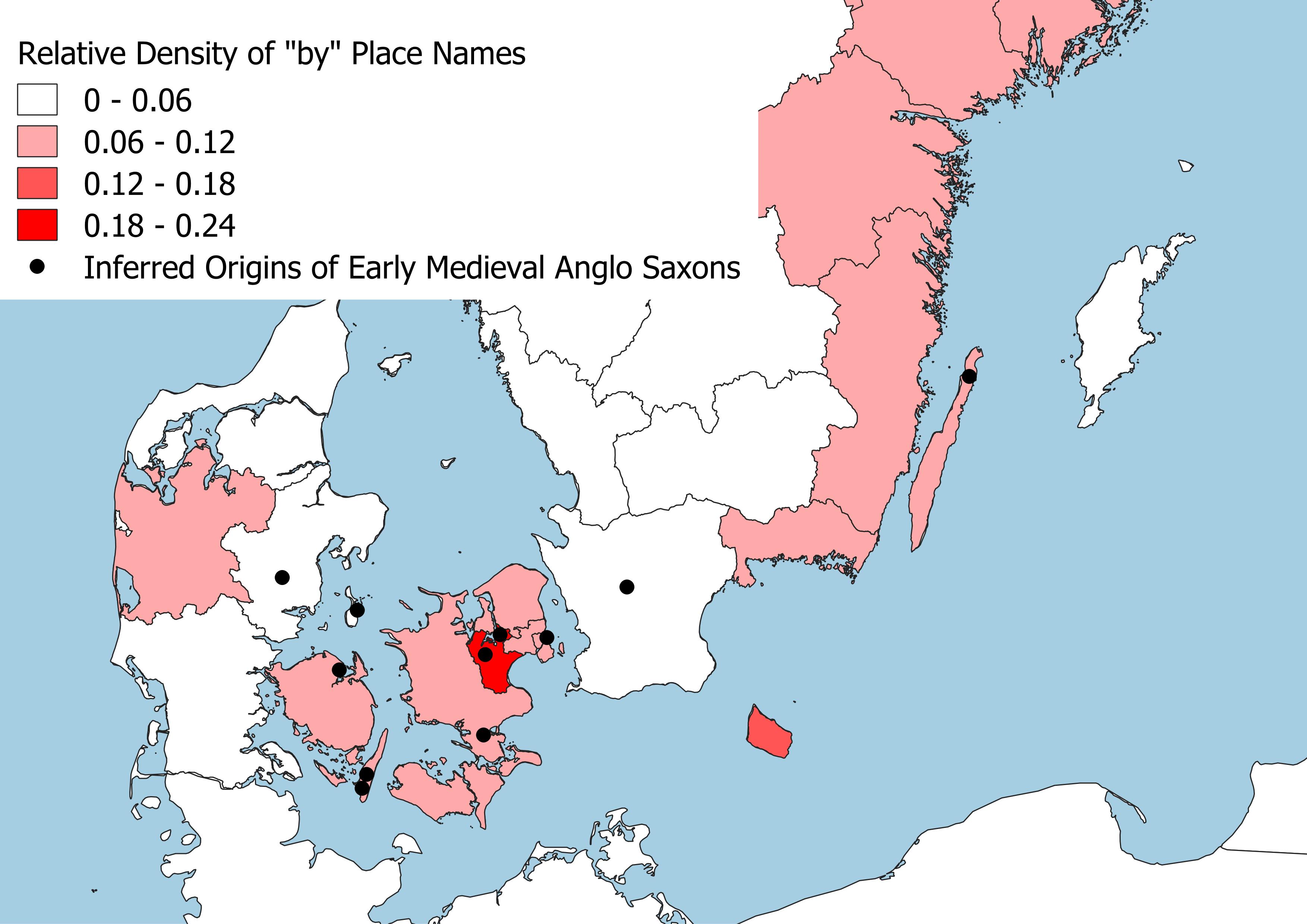

In England place names containing the element “by” are abundant in much of Lincolnshire, Leicestershire and Yorkshire (measured as a proportion of all place names). Their most likely origins can be inferred from their distribution in Scandinavia. Their scarcity in other North European Viking age settlements makes it likely that the English “by” place names are pre-Viking. This possibility is supported by the similarity between the “by” place name distribution and the distribution of likely sources of pre-Viking DNA in Scandinavia (my Figure 3). Clusters of both appear in North-East Zealand (near Copenhagen).

There is also some support for Scandinavian DNA origins in pre-Viking English pottery as shown by the Oxford Scholar and specialist in early medieval pottery J N L Myres (1969). See Appendix 3. It is interesting that Myres believed that some of the Scandinavian pottery arrived quite late in the settlement era. If this were the case we would expect less mixing, and correspondingly a stronger signal from the Scandinavian group.

The evidence in favour of a pre-Viking tribal migration of Scandinavian people into England is mounting. Myres found substantial amounts of pottery. Gretzinger et al found substantial amounts of ancient Scandinavian DNA in pre-Viking England. Leslie et al (2016) used modern DNA and found no evidence for a second wave of mass immigration after the initial Anglo-Saxon conquest. I found that “by” names, so common in parts of England were largely absent from other north European settlements. So what is the evidence in favour of a Viking age origin for the extensive distribution of Scandinavian place names, and does it matter?

The evidence amounts to a couple of much quoted sentences in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. These tell us that elements of the Great Heathen Army, after spending 9 years rampaging around Britain, and presumably living off the land eventually settled down in East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria (where they grew their own food, presumably on the estates they had taken over). This is weak evidence for a mass Viking age immigration as authors like Sawyer (1971), p209 have noted. It matters because the distribution of Scandinavian place names is taken as a proxy for Viking Age settlements. Perhaps less importantly it also matters because the Scandinavian influence on the English language is usually attributed to the Viking age conquests. If widespread pre-Viking Scandinavian settlement had occurred, then the re-integration of Northern and Western Germanic in the common speech of England could have been a much longer process.

Much of the information in this article has been reproduced in accordance with the requirements of the Creative Commons agreement, with acknowledgement to Gretzinger et al 2022

Gretzinger, J. et al., 2022.The Anglo-Saxon migration and the formation of the early English gene pool Nature Springer Nature. Retrieved 2023, Copyright © 2022.

Leslie, S., Winney, G. & Hellenthal, D., 2015. The Fine-Scale Genetic Structure of the British Population. Nature, pp. 309-314.

Myres, J. N. L., 1969. Anglo-Saxon Pottery and the Settlement of England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sawyer, P. H., 1971. The Age of the Vikings. 2nd ed. London: Edward Arnold.

Apple Down, Chichester, West Sussex

Dover Buckland, Dover, Kent

Widemouth Bay, Bude, Cornwall

Fox Holes Cave, Clapdale, North Yorkshire

Eastry Updown, Dover District, Kent

Ely, East Cambridgeshire, Cambridgeshire

Hartlepool, Olive Street, Unitary Authority Hartlepool

Dover Hill, Folkestone, Kent

Hatherdene Close, Cherry Hinton, Cambridgeshire

RAF Lakenheath, Eriswell parish, Suffolk

Lincoln Castle, Lincoln, Lincolnshire

Newquay, Crantock, Cornwall

Norton, Bishopsmill, Stockton on Tees

Norton, East Mill, Stockton on Tees

Oakington, South Cambridgeshire, Cambridgeshire

Polhill, Maidstone District, Kent

Rookery Hill, Bishopstone, East Sussex

Sedgeford, King's Lynn and West Norfolk, Norfolk

West Heslerton, Ryedale District, North Yorkshire

Wolverton, Radcliffe School Mid-Saxon Cemetery, Borough of Milton Keynes

Worth Matravers, Football Field, Dorset

Liebenau

Hiddesdorf

Dunum Lower Saxony

Issendorf

Drantum

Schortens

Zetel

Haeven

Lejre

Besser

Alken Enge

Trekroner

Barse

Hessum

Bodkergarden

Kumle

Gerdrup

Oland

kane

P95- p96. Northern Kent (probably first half of 5th century, similar to pottery found in Esbjerg (Western Jutland), Drensted (Western Jutland), Ribe (Western Jutland), Rubjerg (Northern Jutland).

P99. Yorkshire, Lincolnshire and East Anglia, first half 5th century, similar to pottery found in Danish Anglia as well as some Anglo-Frisian pottery.

P103. Deira and Lindsey, second half of fifth century, similar to pottery found in southern Scandinavia.

P111. Sussex, fifth century pottery with similarities to Norwegian pottery.